Remember the last time you bought a piece of furniture or a kid’s toy that had ‘some assembly required’ printed on the box? As we all know too well, after the box opens, that ‘some assembly’ is a blatant lie! I always rummage through the boxes to get the instructions and start identifying parts (a procedure of sorts) due to my numerous mistakes with assembly. I recently bought a kid’s toy that came with a set of assembly instructions that was about 12 pages long for about 50 pieces. I was initially quite happy with the weight of the guide because I thought there would be sufficient instructions to accurately assemble the toy.

Once I opened the book, I realized that I was completely wrong. All but one of the pages were in languages I don’t speak! The single page for this complex assembly had pictures that were too small to understand, not enough detail to differentiate pieces, and obviously not informative enough for the assembly of the toy! The front of the box provided more help than the waste of paper used for instructions! So, after four hours and six unused parts, the toy had taken its roughly intended form, as per the front of the box, and held mostly together through the first use. This isn’t a review site, so I’ve left my more thorough thoughts for future Amazon shoppers to use as a guide.

My experience with these bad instructions is just the tip of the iceberg of a serious problem. This was a human performance nightmare! This was the first time I had performed this task. This task had a procedure but I had no idea how to accurately use it. I’ve had plenty of experience assembling widgets of various complexity. However, even with a good set of instructions things have still gone wrong. I assembled a desk once where I got a couple of the panels backwards and didn’t realize the error until the last step of the procedure where all of the subsections went together. I went back and reviewed the instructions and box picture (!) and still struggled to identify how I should have known which way the panels should have gone.

“They shoulda known that!”

The instructions that come with products that we buy are procedures. We usually don’t think of them that way but they provide us guidance for operating or assembling a widget and that’s what we use procedures for in the workplace. From these similarities, we can translate our personal experiences and lessons-learned at home into the procedures that we use in the workplace. These experiences, and errors, from home are very relatable to the first time use of a good procedure in the workplace. Even with all of the pictures and directions that can be stuffed into a procedure, there still may be some aspect of a task that is not clear. We also assume that the task will be done correctly and are surprised when a first-time performer does something wrong. My favorite part (sarc!) of this process is when the management says “they should have known” something or other about the task. When someone says “they should have known” my first response is, “why should they have known that?” If someone hasn’t been trained on a task, why should they have known it?

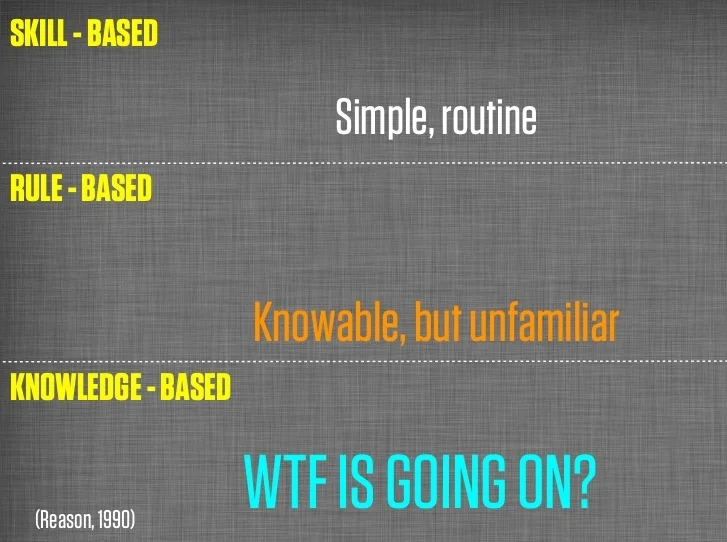

Even if tasks are simple, from our human performance training, we know that there are 3 levels of knowledge; skill-based, the least error-prone tasks; rule-based; and knowledge-based, the most error-prone tasks. Skill-based tasks typically have been done many times before and the performer knows how to do it well. These tasks typically have only a small number of steps. Rule-based tasks are something that we’re familiar with and have been done before. These tasks are typically of moderate complexity or are performed several times a year. Knowledge-based tasks are often a unique situation or performed rarely and require conscious thought to be performed. These tasks are typically complex or, which shouldn’t surprise any of us, a first-time evolution. That’s why we get so many errors for first-time performance of a task and why I people say “they should have known.” When you have to think about every step of a task, it’s easy to leave something out or get confused and do something wrong. Remember my last post about the backwards, upside down valve (add link)? That was also a knowledge-based task, too.

To alleviate these situations and prevent meetings where someone is bound to say, “they should have known,” we need to ensure that we train our employees to use the procedures we have. In almost all situations in the workplace, especially the industrial workplace, the potential outcome of our actions has much more significant repercussions than a poorly assembled toy or a backwards desk panel. Procedures are intended for risk-mitigation. If we aren’t training our employees on how to use their procedures then we’re not mitigating our risks and we’re also putting ourselves, our employees, and our companies in danger.